Ovation

Local literary legend finds her voice by interpreting the words of others

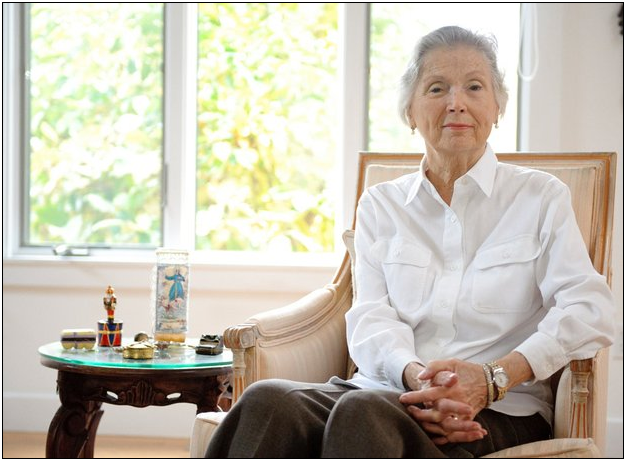

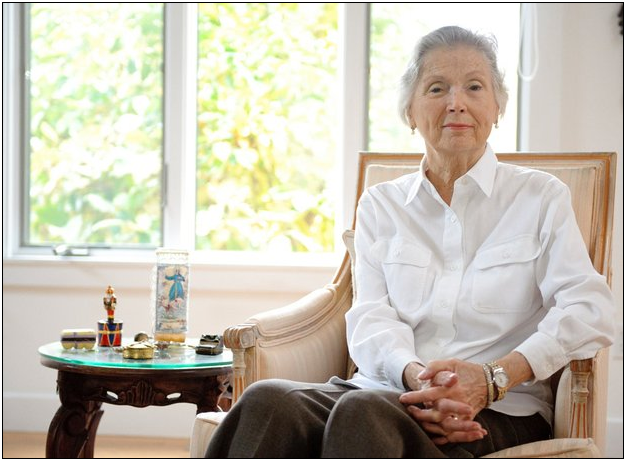

Margaret Peden has spent her career translating Spanish and Latin American works into English. Ryan Henriksen | Buy this photo

It could be called a continual set of puzzles to unlock or a frustrating but essential quest for beauty: the search for a perfect translation.

“We who have attempted a translation often disagree in both meaning and expression. I believe nevertheless that there is a perfect translation, and that it lies among the lines of all the versions produced by diligent and sincere ‘readers,’ ” said Margaret Sayers Peden, professor emerita of Spanish at the University of Missouri, in the introduction to one of her works. Near the end of a decadeslong career translating Spanish and Latin American literature into English, Peden was recently awarded the prestigious PEN/Ralph Manheim Medal for Translation. She traveled to New York City to accept her award this week, surrounded by such authors as E.L. Doctorow, Barbara Kingsolver and Susan Nussbaum. Only a handful of translators have been recognized with the award since its inception.

Peden, known by many simply as “Petch,” was born in West Plains and attended MU for her degrees in Spanish. She began her translation career somewhat by chance in the latter part of the 1960s. At the time, she was working on her Ph.D. and came across a small novel by the playwright Emilio Carballido. She told her husband, English Professor William Peden, how interesting it was.

“And he said, ‘Well, you know I can’t read Spanish. Why don’t you translate it?’ ” she remembered. She did — “and I found I loved it, so I just kept doing it.” Peden has translated some 65 books, including most of Isabel Allende’s novels and nonfiction works, books by Carlos Fuentes and Octavio Paz, the writings of intelligent and progressive 17th-century nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Juan Rulfo’s novel “Pedro Páramo,” and, most recently, Fernando de Rojas’ “Celestina,” a turn-of-the-16th-century work of Spanish literature second in cultural significance only to “Don Quixote.”

That work, published by Yale University Press in 2009, earned Peden the Lewis Galantière Award, sponsored by the American Translators Association. “Celestina” was one of the more complicated works she has translated, Peden said, because of the centuries-old language and the Spanish history she had to research. But she appreciated the challenge of immersing herself in the world from which the tome emerged, and the resultant English translation remains complex in its tragicomic ironies yet is accessible to today’s readers. In comparison, another work Peden said is one of her favorites is Allende’s contemporary memoir “Paula,” which tells the story of her daughter Paula’s coma and subsequent passing, mixed together with vivid, poetic stories of Paula’s and Isabel’s own history and ancestry.

When Peden first began her translation work, she was teaching Latin American literature at MU. Translation courses at universities were not very common, and she did much of the work on her own time. Later she would strive to teach her own students to unearth the true essence of each text while translating, rather than simply switching the language word for word. “I tried to teach my students this: You have to scrape off the words, get down to an under-level. … That’s where the meaning is, below the words,” she emphasized. Gregory Rabassa, a friend and fellow translator, said in Peden’s PEN award statement that her translated characters “speak as they would have had they been born to English and their authors likewise acquire a style in their transformed tongue that is true to what they say or are trying to say.”

Peden will often rewrite five to 10 pages of a work in Spanish at a time, using a combination of both Spanish and English. Then she returns to the beginning and revises, looking up the words she doesn’t understand, and revises again. By the time each book is published, she has pored over it numerous times. She has another hard rule that she judges her work by, a telling aphorism Rabassa passed on to her: “‘You can’t commit the sin of improvement.’ That’s not the point. If it’s a bad book, it has to be a bad book!” she reasoned with a laugh. “Though I try not to ever get one.”

Translating a work is a constant solving of puzzles, Peden noted. “And that’s one of the nice things I love about it, is that you don’t get bored. You can’t get bored.” Often she does as much as or more research than academic writers and critics for the works because she must learn everything she can about a book’s historical and cultural contexts, the way the Spanish language is used in those contexts, and the specific vocabulary and voice of each author — not to mention the voices of all the author’s characters, if applicable. “I don’t have a writing style except the ones I pick up from the books I translate,” Peden explained. “I have done a lot of writing, but that’s not my thing. I’m just better at hearing what somebody else writes.” Indeed, Roberto González Echevarría, Yale professor of Hispanic and comparative literature, praises her ability to nearly turn “herself into” the writers she translates. In his introduction to “Celestina,” he said Peden “is today the most accomplished active translator of Spanish-language literature into English.”

People don’t typically realize how dependent they have been on translations, Peden mused about the often-overlooked role of a translator. “Look at our Western civilization. It came to us in translation: the Greeks, the Bible, all these things.” She is proud to be part of that long tradition and recognizes that she has gained other benefits from walking the “road less traveled” of her chosen career, including a greater tolerance for elements of other cultures she might have felt impatient with before. But Peden added perhaps the best part of her journey has been the relationships she has gained — with her authors, with translators and with other readers who love and respect good literature as much as she. “I’m lucky, the people I’ve met,” she said.

Jill Renae Hicks has previously written arts features for the Tribune and now works as a freelance writer, editor and illustrator. She is interested in the local literary and writing scene and how it connects to the rest of the arts and the greater Columbia community.

Reach Jill Renae Hicks at 573-815-1714 or e-mail jrhicks@columbiatribune.com.

This article was published on page C5 of the Sunday, October 28, 2012 edition of The Columbia Daily Tribune with the headline “Found in translation: ” Click here to Subscribe.

You may be wondering why I posted this well-written article on Margaret Peden, legendary literary translator. There is a personal connection here. Petch is my sweetheart Sally Peden’s step-mother. Petch will be celebrated for her lifetime achievements in translation at Missouri University this Friday, November 16, 2012. I asked her if there was an article about it and she mentioned this one, which came out two Sundays ago. Petch is a great lady, and its always fun being around her and her husband Robert Harper.

UPDATE: Sept 2, 2020: I received a call from a family member that Petch had passed away this summer. I had been wondering how she was doing since it had been several years since we had spoken. Her obituary was posted online July 12, 2020 in The Columbia Daily Tribune, Columbia, MO. You can read it here: Margaret “Petch” Sayers Peden, 1927-2020. It was also published July 9, 2020, courtesy of the family, in the Columbia Missourian: Margaret ‘Petch’ Sayers Peden, May 10, 1927 — July 5, 2020.

I saved it as a PDF with the photo, which I cropped here. You can download it below to get a fuller appreciation for this incredible woman. Here are some of the professional highlights:

Margaret “Petch” Sayers Peden, professor emerita of Spanish at the University of Missouri and renowned translator of Spanish-language literature, passed away at her home on July 5, 2020, surrounded by loved ones. She was 93.

Petch was among the preeminent scholars in the field of translation and one of its greatest champions, working to propel it as a creative effort in its own right.

During and after Petch’s teaching career at the University of Missouri, she continued translating literary works from Spanish to English. She was considered to be one of the leading translators of her time. As a perfectionist, she felt that words could be “unreliable,” “slippery,” “stretchy, treacherous.” She once said, “We [translators] should be evaluated as an actor or opera singer is evaluated, as performing a previously established text.” This acknowledged the complexity of her job as translator, that it was never just finding the English word for the Spanish one, but getting underneath to the essence, or soul of a work. This genius of elucidation is why she was asked to translate works by Carlos Fuentes, Isabel Allende, Pablo Neruda, Octavio Paz, as well as bringing to life her personal hero, the 17th century nun Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz, who, like Petch, was “a woman of genius.” Her deft approach resulted in numerous literary awards including the PEN Translation Prize in 2004, the Lewis Galantiere Translation Prize in 2010 and the PEN/Ralph Manheim Medal for Translation, a lifetime achievement award, in 2012, among many others.

Over five years later, I came across another article, a more personal one, written by Cathy Salter, published Jul 22, 2020 by Boone County Journal: A Literary Remembrance of Margaret Sayers Peden. Cathy and her husband Kit met Petch over two decades ago at a Peden Prize event—an annual event honoring her first husband, Dr. William Peden, (Sally’s father) who founded “The Missouri Review.” She wrote: “More recently, books connected us again when Petch and her second husband, Robert Harper, became regulars at monthly book talks that Kit organizes for Osher Lifelong Learning.” (I’ll paste a little more.)

It was during those monthly Saturday morning gatherings of local writers, published authors, book enthusiasts, poets, and local publishers that we came to know Petch as a true lover of words and the craft of writing. This grand lady has translated over 65 works by esteemed Spanish-language writers—including Isabel Allende, Carlos Fuentes, Octavio Paz, and Pablo Neruda. In 2012, we proudly shared the news that Petch had been awarded the coveted PEN-Ralph Manheim Medal for Translation, a lifetime achievement award.

Early the following year, Petch reluctantly agreed to do a book talk, saying it would likely be her last. The morning of her talk, Petch took her audience of 65 fellow lovers of language on a mesmerizing, unexpected literary journey. She opened by asking, “In the past year, how many of you have read a poem?” A few hands went up. She then proceeded to introduce us to two of her favorite Spanish-language poets.

Click the title to finish this wonderful article, also saved as a PDF. It was previously published July 20, 2020 in the Columbia Daily Tribune: Notes From Boomerang Creek: A literary remembrance of Margaret Sayers Peden. Both CDT articles are behind paywalls, why I found other options.

Taylor & Francis published an Obituary in Translation Review Volume 107, 2020 – Issue 1, by Rainer Schulte, Page 135, online Nov 9, 2020: MARGARET “PETCH” SAYERS PEDEN, 1927-2020. They concluded: “The community of translators celebrates the achievements and elegance of Petch Peden.” and encouraged readers to see her obituary in the Columbia Missourian, mentioned above: Margaret ‘Petch’ Sayers Peden, May 10, 1927 — July 5, 2020. (PDF)

Friday, November 14, 2025, Cathy Salter posted this updated remembrance with photos: Celebrating Margaret Sayers Peden. She emailed me, as I had requested, with the link, saying: “Today is the day my weekly blog is published. This one is for the good folks who attended monthly Saturday Morning Book Talks gatherings in Columbia that my darling husband Kit organized for over a decade. As I send it to you, I have a copy of my book Notes From Boomerang Creek in my lap opened to a page with a comment that means the world to me as a writer who loves swimming in a sea of words and memories.”

Cathy added Petch’s blurb for the book from the top of the page under Praise for Cathy Salter’s Notes From Boomerang Creek. “In this delicious book Cathy Salter leads us through the full scope of life’s adventures. Columbia, Missouri has known her for years, and now we share her with a wider world of readers. We follow her down country roads, into U.S. and foreign cities, and enter intimate corners of her life. Be grateful to be showered with luminous words as you turn these pages.” — Margaret Sayers Peden, Award-winning Translator, 2012 Winner of PEN/Ralph Manheim Medal for Translation. The book is available on Amazon.

— Written and compiled (citing sources) by Ken Chawkin for The Uncarved Blog.